By the time Marcus Arroyo arrived at Wilson Recreation Center for his first intramural basketball game of the season in late January, it already was underway, and he was in a hurry. For months, he’d been juggling clinical rotations as a student in the Duke Physician Assistant program and working with a youth group at his church, and all that meant a late arrival for his weekly game with “The Dad Bods.”

Marcus had just taken off his shoes and was preparing to change out of his work clothes when a teammate burst into the room.

“Marcus! We need your help!” he cried.

Their friend and teammate, a 35-year-old physical therapist at Duke, had collapsed on the court in the middle of the game and appeared to be having a seizure.

And Marcus, everyone on the team knew, was deep into his medical training and would know exactly what to do.

As Marcus hurried to the court in his socks, all the possible scenarios flashed through his mind: A stroke? Seizure? Heart attack?

“I’m trying to tell myself to be calm,” said Marcus, 27. “Because I know in a lot of these circumstances, one of the worst things you can do is emotionally freak out – which would be really easy to do, right? Anyone would, really. It’s super-easy to get overwhelmed and think of the worst-case scenario.”

He didn’t know that Wilson Recreation Center on West Campus would be filled with people ready and trained to help and equipped with what he’d need to avert the worst-case scenario.

The intramural supervisor at Court 3 who was steps away when the physical therapist collapsed knew CPR. So did the facility monitor and the front desk attendant – and every employee at the center, for that matter. Wilson has six Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) spaced throughout the 99,000-square-foot building – an increased number from a little more than a year ago when an internal evaluation determined the facility needed more.

And although no one can recall such a medical emergency happening in Wilson in recent memory, there’s a protocol and plan in place for what everyone should do if something happens.

“My biggest takeaway was how trained our staff was,” said Cliff Merritt, Duke Recreation & Physical Education Director of Aquatics and Risk Management. “I was really happy with the response of the team, the professionalism of them and how everybody pulled together to help with the situation.

“It was definitely a team effort, and the staff just did an amazing job.”

And all of it saved a life.

'This Can't Be Happening'

As Marcus rushed to the court, Pankit Ghanshyambhai Pandya was kneeling next to the Duke physical therapist. Pandya, who recently graduated from the Master of Engineering Management program, was working as the intramural supervisor at The Dad Bods’ game on Jan. 23 when the man crumpled to the floor about 5 feet away.

All that Pankit knew was that the collapsed player needed help. He called 911.

When Marcus arrived at his friend’s side, he discovered he wasn’t conscious. He wasn’t breathing, and he didn’t have a pulse.

Marcus started CPR. As he counted out 30 chest compressions and two breaths, his mind whirled, again: How long has he been out? Is someone getting an AED? Is someone calling 911?

And in the back of his thoughts, this one: Is this real? This can’t be happening.

“Working in medicine, you know giving CPR is kind of always a possibility,” Marcus said. “But you would never think of doing it to someone that you know.”

Pankit had rushed to the front desk to retrieve an AED. As he explained what was happening to everyone, Wilson Facility Manager Ty Johnson, a Duke pre-med student, jumped into action, too. He grabbed another AED from the third-floor weight room. The front desk attendant called 911, too.

Marcus had administered two rounds of CPR when an AED appeared at his side. He realized he needed to use it.

Using an AED

Cliff Merritt, the Director of Risk Management, said AEDs are fairly easy to use. “They tell you exactly what to do,” he said. “You just open it up and follow the prompts for the most part.”

Although Marcus had been trained on how to use an AED, he’s never had to use one on someone who needed the electric shock to survive. Neither had Pankit, Ty Johnson or the medical resident in the gym who rushed over to help. But they all worked together to untangle wires and attach the AED.

“No pulse evident,” the AED said. “Shock advised.”

Someone pressed a button, administering the shock to the physical therapist, but his pulse didn’t return.

Marcus resumed CPR and was preparing to hand over the task to Ty when someone noticed the player’s chest rising and falling. Marcus checked for a pulse again and this time, it was there.

Marcus asked his friend to squeeze his finger if he heard him. He squeezed just as Emergency Medical Services arrived.

In all, about 12 minutes passed from the time the player collapsed to the time his heart began beating on its own, again. Doctors later told the physical therapist that someone in those circumstances has about a 3% chance of survival. The physical therapist agreed to be interviewed for this story but asked not to be identified.

'A Miracle'

The physical therapist had experienced something known as sudden cardiac arrest, which is the abrupt loss of heart activity due to an irregular heart rhythm. Although he had never had a heart episode before, he had a mechanical aortic valve inserted about four and a half years ago, he said, after a routine doctor’s visit detected a heart murmur that revealed a congenital heart defect.

He’s participated in triathlons and played basketball in the years since without any issues.

After the Jan. 23 incident, doctors discovered scarring on the physical therapist’s heart, possibly caused by the mechanical valve. No one knows why it happened when it did, but the scarring disrupted the electrical impulses of his heart. After several days at Duke University Hospital, he had an internal cardiac defibrillator implanted – which will act like an automatic, internal AED if his heart ever goes into another dangerous rhythm.

Marcus doesn’t want to be called a hero. He insists the response was a group effort with the right people and equipment in place that saved his friend’s life. Both Marcus and the physical therapist are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and believe something greater was helping, too.

“During that time, I definitely felt like I wasn't alone,” Marcus said. “Obviously, I was in a gym with many people around me, but I definitely felt something helping me remain calm and helping me stay focused.

“He tells me that I saved his life and I believe it,” Marcus continued. “I’m glad I was there. I know I was involved, I know was a big part of it, but I still want to give credit and have humility and accept and acknowledge that it wasn’t just me. It was a group effort.”

Michael Howard, Senior Director of Recreation and Physical Education, said the response by the Wilson Recreation Center staff was “phenomenal.” In his 13 years at Duke, he has not seen such a serious emergency or the use of an AED in the center, but “the response time we had was really strong and a credit to our team.”

Even so, the staff at Wilson Rec Center has had an increased focus on CPR and AED training in recent weeks. Two weeks after the incident, the Brodie and Wilson Rec Center staffs reviewed medical emergency procedures and plans to ensure everyone understands the best protocol.

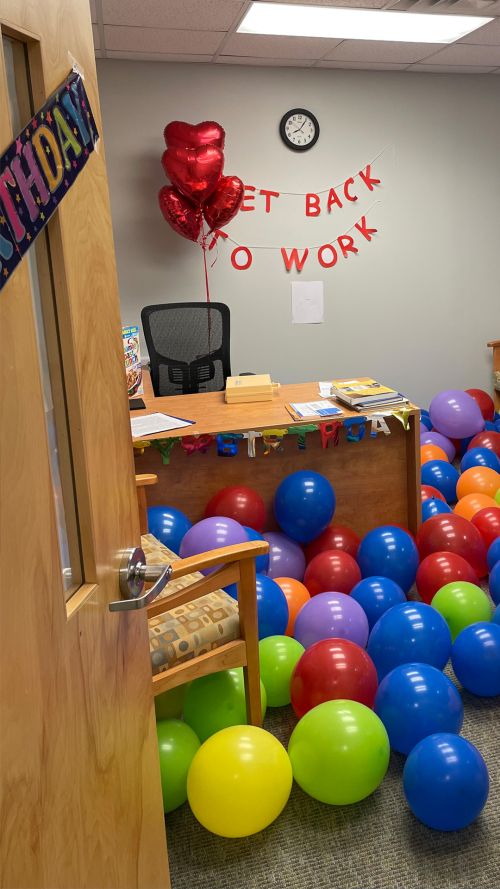

A week after the physical therapist was released from the hospital, he celebrated his 36th birthday. It was a wonderfully low-key day with his wife and two young daughters, he said. Two days later, he returned to the office where he’s been a Duke physical therapist for nearly eight years to find the room stuffed with balloons to celebrate his birthday. His Duke co-workers also hung up a sign welcoming him back to the office that read, “We are heartbroken without you.”

Later in February, Managing Director of Recreation Facilities Chris Policastro presented him with a signed basketball from Duke men’s coach Jon Scheyer.

“I do think that in many ways, it was a miracle to have so many things in place,” the physical therapist said. “Marcus had every reason to not be there that night, he was helping teach some of the youth in the church and he had a test the next day. But he felt very strongly like he needed to be there.

“It couldn't have happened at a better place, with the AED present. The response from Marcus and from the others there was just spot-on from timing as they went into their training. I'm glad that I was with trained professionals where there was an AED, and close to Duke, because it all just worked out really well.”

View the full story here.

Story provided by today.duke.edu.

Author: Jodie Valade, Working@Duke Senior Writer

Image credit: Travis Stanley